I’m going to ask you a couple of questions. If you answer all of them correctly, and understand why - good job! this post is not for you.

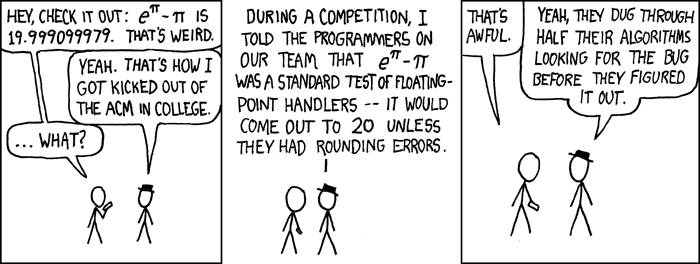

Otherwise, If you’re a normal human being, consider reading this post. It’ll save you hours of useless debugging. Honestly, If the engineering who built Ariane V read it (and set their compiler to warning as error) their rocket wouldn’t blow up.

What’s the answer? yes or no?

float x = 0.7; |

What will be printed?

float x = 4 / 3; |

What’s the answer? yes or no?

float x = 1.0/3.0; |

Are both lines equal?

float x = 0.20; |

Now that I’ve got your attention, lets go over the answers real quick. Once you get to the end of this blog post, You’ll understand them fully and be able to impress your coworkers with useless knowledge.

float x = 0.7; |

output: no.

float x = 4 / 3; |

output: 1.000

float x = 1.0/3.0; |

output: no.

float x = 0.20; |

output:

0.20000000298023223877 |

IEEE 754

From Wikipedia’s IEEE Floating Point -

The IEEE Standard for Floating-Point Arithmetic (IEEE 754) is a technical standard for floating-point computation established in 1985 by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE).

The standard addressed many problems found in the diverse floating point implementations that made them difficult to use reliably and portably.

TL;DR: A standard for floating points. nowadays, supported on most hardware.

Binary Fractions

Let’s take a look at the following binary fractions:

| number | binary |

|---|---|

| $$ 5\frac{3}{4} $$ | 101.112 |

| $$ 2\frac{7}{8} $$ | 10.1112 |

| $$ 5\frac{63}{64} $$ | 0.1111112 |

Think about that - binary fractions? how can binary digits represent fractions?

Well, they don’t. Many numbers are an estimation of the real number, and the more bits you have for the fractions part, the more precise it is.

| value | binary | float |

|---|---|---|

| $$ \frac{1}{3} $$ | 0.0101010101[01]… | 0.33333334326744… |

| $$ \frac{1}{5} $$ | 0.00110011[0011]… | 0.20000000298023… |

| $$ \frac{1}{10} $$ | 0.000110011[0011]… | 0.10000000149011… |

The standard

s: The sign bit. It determines if the number is positive or negative.exponentorE: The “weight” of the number in powers of two.mantissa: The fraction part, normalize to1.xor0.x.

As you can see, you can control the accuracy of the number:

Bigger exponent -> You can represent a bigger number

Bigger Mantissa -> The fraction will be more precise

As for the standard: A double precision floating point (aka, double) is much more accurate than a regular floating point (aka, float).

Bias

the exponent part needs to represent both negative and positive powers (i.e, fractions). To do that, the standard introduces the bias.

basically, the bias is used to represent the exponent as an unsigned int:

$$ bias = {2^{sizeof(exponent) - 1}} - 1 $$

for instance, in a floating point, the size of the exponent is 8 bits, so the bias would be:

$$ {2^{(8 - 1)}} - 1 = {2^7} - 1 = 128 - 1 = 127 $$

That means that for a floating point, the exponent range would be cut in half, to represent both negative and positive numbers.

Deep Dive

Let’s break down the number -118.625

We’re talking about a negative number, so the sign bit is set.

Now, for the technical part:

- $$ {118_{10}} = {110110_2} $$

- $$ {0.625_{10}} = \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{8} = 1 \times {2^{ - 1}} + 0 \times {2^{ - 2}} + 1 \times {2^{-2}} = {.101_2} $$

So our number would be:1110110.101

The fraction part is made of the .x part of the 1.x number.

So we “shift” 1110110.101 6 bits left, and get the following mantissa: 110110101.

What about the exponent? because we shifted the number 6 bits left, the exponent would be 6, or 110 in binary. But we need to include the bias as well.

$$

bias = {2^{8 - 1}} - 1 = 127

$$

$$

e = E + bias \to 6 + 127 = 133

$$

which is 1000101 in binary.

A couple of pointers (haha) before we get to the categorization…

Eis the original exponent = 6.eis the biases exponent = 133.

Categories of numbers

Remember I said earlier that the mantissa holds numbers in the form of 1.x and 0.x? well, these are the two categories.there are more.

- If both the exponent and the mantissa are zero, then the number is

0. - If the exponent is zero, but the mantissa is not, the number is

0.x. - If both the exponent and the mantissa are non zero, the number is

1.x. - if the exponent is filled with ones (111…) and the mantissa is zero, the number is +-infinity (determined by the sign bit)

- if the exponent is filled with ones (111…) and the mantissa is non zero, the number doesn’t exist. for instance:

sqrt(-1).

Really small numbers that can’t be represented in the 1.x form (normalized), are called denormalized.

Denormalized numbers

Let’s take a look at the following two numbers: x and y.

x will be the smaller possible normalized number in float

$$ x = 1.0000 \times {2^{ - 126}} $$

y will be another really small number:

$$ y = 1.1 \times {2^{ - 126}} $$

If we subtract x from y, we’ll get $$ 0.1 \times {2^{( - 126)}} $$. That’s a smaller number than is possible in the normalized spec.

But that’s a REALLY small number, so why not just round it to zero?

Well, if we do that, that the common assumption that x - y = 0 if and only if x == y breaks. To make sure we don’t blow up the universe, we need to find a solution to gradually move between normalized numbers to zero.

The solution? use a fixed point representation, where the point is the smaller possible exponent (-126). The bias in this situation should be the smallest possible number, and E accordingly:

$$ E = 1 - bias $$

Now, if we drop the 1.x requirement that normal numbers have, and fix the exponent to -126, we’re able to represent even smaller numbers than 1.x allows, in the form of:

$$ ({a_1}{2^{ - 1}} + {a_2}{2^{ - 2}} + … + {a_{23}}{2^{ - 23}}) \times {2^{ - 126}} $$

! why 23? because in doubles, the fraction part holds 23 bits.

specifically, we’ll be able to represent y-x. We can’t move the point beyond -126, which means that any further calculation can’t take the number any lower.

Adding the denormalized representation allows floating points to represent even smaller numbers than the normalized spec allows.

Rounding

Sounds like a big deal, but really all the means is:

- Calculate the result

- Round it to the requested precision

The standard supports a number of rounding algorithms:

- Zero

- Round Up: +infinity

- Round down: -infinity

- Nearest even

The default is nearest even, you can’t really control that easily.

Rounding is a big mess, and the culprit for many nasty bugs.

If the result overflows and/or rounding occurs, simple arithmetic might not work:

$$ (3.14 + {10^{10}}) - {10^{10}} == 3.14 + ({10^{10}} - {10^{10}})? $$

The former is not equal because $$ 3.14 + {10^{10}} $$ is rounded!

That means that when we cast one type to another, we need to make sure we don’t overflow. otherwise, rounding occurs and might make our code blow up. literally.

What happened? a double was casted into an int which caused the whole system to go haywire. You can read more here.

Optimizations

Theoretically, the compiler can take this stupid piece of code:

x = a + b + c; |

and optimize it:

t = b + c; |

But because we might overflow, the associative nature of numbers doesn’t work here. In other words, the compiler won’t perform any optimization!

gcc has two flags that optimize floats:

-fassociative-mathwhich allows to re-associate floating point operations-ffast-mathwhich allows even more aggressive accuracy vs speed trade-offs.

Back to the questions

float x = 0.7; |

x is a float, but 0.7 is not. The binary representation of them is different, which causes the confusion.

float x = 4 / 3; |

4 and 3 are both integers, / operator divides them as integers, and returns an integer as the result, then is implicitly casted to a float.

float x = 1.0/3.0; |

(x+y) - x lost some precision when x was added and subtracted, so even though mathematically it looks correct, the binary estimation is different. Take a look at Compare floats to three decimal places to see a way to mitigate that.

float x = 0.20; |

Again, both numbers are represented differently in memory.

Summary

- Be VERY careful when casting between types.

- Don’t ignore compiler warnings. Actually, set your compiler to warning as error

- Test everything. especially delicate code (sounds obvious right? it’s not!)